When one world brushes another, asking the right question can be magic….

This short story was acquired for Tor.com by Tor Books editor Paul Stevens.

Craig Chess answered the phone on the second ring. It was his landline, and nobody called on that unless it was an emergency. He saw that the clock read 1:30 a.m. as he said, “Hello?”

After a pause, a woman with the slow drawl of East Tennessee said, “May I speak with your daddy?”

“My daddy?”

“Yes, the Reverend Chess.”

Craig sighed. He knew he looked young; apparently he even sounded that way. “Ma’am, this is Reverend Chess.” He turned on the light and reached for the pen and pad he always kept handy. “What can I do for you?”

“Oh, I’m sorry, didn’t recognize your voice. I didn’t think you had any children.” The last word came out chidrun.

“No, ma’am, no kids. I promise, it’s me.”

“Well, this here is Lula Mae Pennycuff over to Redford’s Ridge. I hate to bother you at such an hour, but my daddy’s on his last breath and he’s asking for a preacher. You’re the only one we know.”

Craig tucked the receiver under his chin and pulled up the contact list on his iPhone, where he also kept notes on the people he visited. Lula Mae Pennycuff and her husband Johnny lived with her father, known as Old Man Foyt to everyone. The married couple attended Craig’s church on occasion, but Craig had never met the old man. “Of course, Mrs. Pennycuff. Is your daddy a Methodist?”

“Oh, he ain’t no denomination. He ain’t set foot in a church for thirty years. He’s just scared, now that he’s facing the pearly gates. He wants a man of God to tell him he ain’t going to hell.”

“I can understand that. You live out on Starling Road, right?”

“That’s a fact, down in the hollow past the railroad bridge. There’s a big old cow pasture just opposite us. You’ll have to park on the road and walk up the hill to the house, though. I’m afraid the driveway’s full. I’ll turn on the porch light for you.”

“Thanks. Give me . . . oh . . . twenty minutes.”

“I sure do thank you, Reverend.”

“It’s part of the job description, Mrs. Pennycuff. I’ll be praying for him and you all the way.”

He dressed quickly and put on a UT Knoxville cap over his sleep-matted hair. Old-fashioned ministers in Appalachia would never leave the house dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, no matter the hour; then again, old-fashioned ministers in Appalachia had consistently failed to make a go of the Triple Springs Methodist Church. Craig’s congregation had shown slow but steady growth, so he assumed he was doing something right, and trusted his instincts.

He brushed his teeth and touched up his deodorant. He’d already attended a few of these home deaths, always of old (or old-fashioned) people who didn’t trust modern hospitals, or lacked the insurance to be treated by one. The latter situation infuriated him, but he had respect for the former. One of the greatest dignities of life was choosing how you passed from it.

But that was general, and he could’ve encountered that in any rural parish. What made this situation especially significant was that the Pennycuffs lived across the line, actually in mysterious Cloud County. They were, in fact, the only fully non-Tufa people he knew of who lived there, certainly the only ones who were also churchgoers. And that made this special.

He paused at the door, then hit a particular number on his iPhone. A moment later a woman said sleepily, “Hey, honey. What’s up?”

He got the same little thrill he always did hearing Bronwyn Hyatt’s voice. She was a full Tufa, with the black hair, vaguely dusky skin, and perfect white teeth of all her people. She was also part of the secretive Tufa group known as the First Daughters, and the strongest, smartest, and most beautiful woman he’d ever known. He always found it slightly absurd that she seemed to be in love with a small-town preacher who insisted on holding off sex until they were married. But at the moment, he was just grateful that all of it was true. “Hey. I just got a call from Lula Mae Pennycuff. Old Man Foyt’s on his last legs, and she wants me to come out and pray for him.”

“Are you going?”

“Planning to.”

“Do you need me to come with you?”

“No.”

“Do you want me to?”

“Actually, yes, but this is my job, so I’ll handle it. I was just calling to ask you . . . Well . . . This won’t rub anyone the wrong way, will it? Me coming to minister to somebody in Cloud County? It’s not going to, like, maybe . . . piss off the First Daughters?”

There was a pause. “Well . . . I think it should be fine.”

“But you’re not sure? I mean, you’ve told me stories about why there aren’t any churches in Cloud County, and no offense, but people talk about the First Daughters like they’re a cross between the Carter Family and the mafia.”

He heard her sit up, and tried mightily not to think about how adorable she must look with her hair tousled from sleep. She said, “First, you’d never run roughshod over anyone else’s beliefs, like those old Holiness Rollers did. People here like you, and they respect you. Some of us are even downright fond of you.”

“And second?”

“Second, I can’t imagine the First Daughters doing anything without involving me.”

“That’s less reassuring than you probably think it is.”

“Honey, if I told you not to do it, would that stop you?”

“No. But it might make me more cautious.”

“Well, then, it doesn’t matter. You have your calling, and I respect that. If anybody says anything different, you tell them you talked to me, and I said it was okay.”

He smiled. With Bronwyn on his side, he doubted any Tufa would say boo to him. However their clannish organizational structure worked, she was both respected and feared within it.

“Now go help old Mr. Foyt and let me get back to sleep,” she continued. “Come over for breakfast if you can, Mom and Dad’ll be glad to see you.”

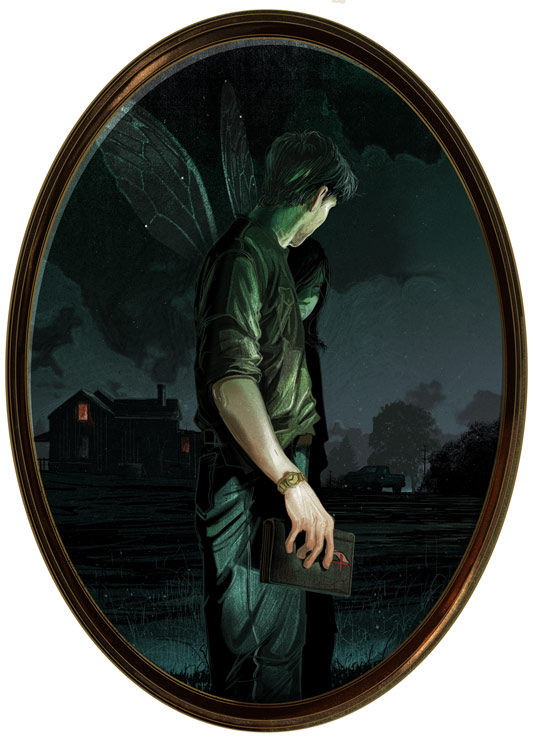

He hung up, still smiling as always when he finished talking to Bronwyn. But as he drove through the night, and felt the familiar little tingle when he crossed the county line, he thought again of what circumstance and strange events had taught him about the Tufa. They had been in these mountains before even the first Indians, keeping to themselves, playing their music, and occasionally . . . well, doing things that he knew weren’t possible for human beings. Fairy was the closest word for them; not the diminutive storybook kind but the ancient Celtic warrior gods spoken of in the Mabignogion and The Secret Commonwealth. And only the tiniest nagging doubt remained for him. What would happen when he was fully convinced of that truth, he couldn’t say.

He found the Pennycuff farm easily, not least because there were a half dozen vehicles in its driveway. He parked just past the mailbox, picked up his Bible from the passenger seat, and got out.

As soon as the door opened, he heard music. It didn’t surprise him: Cloud County was the most musical place he’d ever seen. But abruptly he realized the music came not from the house where the family sat on death watch, but from the other side of the road, where there was nothing but a fence and a wide pasture beyond it. A lone instrument, picking a soft minor-key melody that he didn’t recognize.

He squinted into the darkness. Something—someone—sat on the fence. It was like a person, but half his own height, and far more delicate. Fairy jumped to his mind again as the figure continued to play what seemed to be a small, child-size guitar.

Then, with a flood of relief and renewed confusion, he realized it was a child: a little girl, of about ten or eleven, dressed in jeans and a tank top. She stopped playing and said, in the distinctive Appalachian drawl, “Hello.”

“Hi,” Craig said. “Are you one of Mr. Foyt’s grandchildren?”

She shook her head, making her jet-black hair tumble into her face. She tucked the ends back behind her ears and said, “I’m actually here to see you.”

“Me?”

“You’re the Right Reverend Chess, ain’t you?”

“Uhm . . . just ‘reverend.’”

“My name’s Mandalay Harris.”

Craig searched his memory. He knew the name, but he couldn’t quite find the context. The only “Mandalay” he recalled was the one Bronwyn occasionally mentioned, the woman who led the First Daughters. “Nice to meet you. I’ve heard tell of your mama.”

“Nossir, you haven’t,” she said.

“Your mama’s not the Mandalay who . . . ?” He trailed off, unsure if he should mention what he knew. He didn’t want to get Bronwyn in trouble for violating a confidence, which she really hadn’t done.

The girl chuckled. “Nossir, I’m the Mandalay who.”

They were both silent for a moment. A dog barked in the distance, and an owl hooted. It was ridiculous to think that this kid was someone with power and influence over Bronwyn, a woman who had the strongest will of anyone he’d ever known. And yet, there was an intangible truthfulness that made him, if not believe it, at least consider the possibility. He said, “Well . . . nice to meet you, miss. What’s that you’ve got there, a ukulele?”

“Nossir, it’s called a ‘tiple.’ I got it from Bliss Overbay, and she got it from her grandfather. Easier for me to get my hands around. Do you know Bliss?”

“I’ve met her a couple of times. She’s good friends with my girlfriend.”

The little girl nodded. “That’s her. I hear mighty good things about you, too.”

“Well . . . thanks, I guess.”

“Good enough things I was wondering if I might ask you something.”

“Sure. But it’s got to be quick, I’m needed inside.”

“I know, and this has to do with that, too. Don’t get many situations like this, where a non-Tufa is about to die a peaceful death in Cloud County. It’s kind of a special moment, and not just because of the dyin’.”

She hopped down off the fence, her flip-flops crunching on the gravel. She held the tiple casually, by its neck. “Here’s the thing,” she continued. “Old Mr. Foyt, he’s lived in Cloud County long enough, he’s kind of soaked up the place. He ain’t a Tufa, of course, but he’s not . . . quite a normal human man anymore. He’s a little bit in the middle.”

Craig wished he could see her face more plainly. These mature and self-possessed words, in that little girl’s voice, were strange and, for lack of a better word, creepy.

“A man like that dies in Cloud County, he might, just for a moment, be able to see across things from the Tufa world to his own. He might be able to know something that I’m purely dying to find out, for my own peace of mind and for everyone else’s.”

“And what’s that?” Craig asked.

She sounded weary, with the weight of some responsibility that even an adult would find difficult to bear. “At the end of things, when the last song’s been sung, do the Tufa go up before the same God as the human beings?”

Again the night’s soft orchestra of insects, birds, and distant cries enveloped them. He said, “You may not call it the same name, but I suspect the Tufa god and the Christian God are the same.”

He heard the smile in her words. “You didn’t say, ‘the real God.’”

“It is the real God. And that God can show any face he likes, to anyone he likes.”

Adult, sophisticated amusement rang in her little girl’s voice. “Is that what they teach you in preacher school these days?”

“That’s what life has taught me.”

“But here’s the thing, Reverend, and this is one of our most secret things. The Tufa god doesn’t have a face, or a name. It’s the night winds. The ones in the trees all around us right now. It whispers, it sings, it carries us where it will. We do best when we listen, when we harmonize, when we ride and don’t try to fly against it.”

Despite the summer night’s heat, Craig felt cold certainty run up his spine. He did not doubt this story at all. “That’s . . . sort of how we feel about our God. We do best when we follow His rules and listen for His whispers.”

“Do you think He waits at the end of that tunnel of light, like they say?”

“Possibly. I haven’t died myself, so I can’t say for certain.”

“Then I’d like you to ask that man you’re about to go see, the one who’s about to see your God, a question for me. Right at the last moment there’ll be a caesura; do you know that word?”

“Yes. It’s a pause in music or poetry.”

“That’s exactly right. And that’s when he might be able to see from your world to ours, and all the way to whatever high power waits for him. That’s when I’d like you to ask him something. Will you do that?”

“I can’t say until I know the question.”

“Just what I asked you. Will the Tufa go up before the same God?”

“Uhm . . . at the point you mention, he may not be able to answer questions.”

“He will. Like I said, he’s soaked up a good deal of Cloud County. There’ll be a moment, just before the end. That’s when you ask.”

“Why do you want to know?”

She cocked her head slightly, just enough so that the moonlight at last fell fully on her small face. Craig almost jumped back. Her skin was now wizened, wrinkled, and dried tight like the parchment skin of a South American mummy desiccated by time and arid air. Yet her lips moved and that same child’s voice said, “Because I may never have another chance to get the answer. This sort of conjunction ain’t never happened before, and ain’t likely to happen again. And our world is changing so fast, Reverend . . . I need every bit of new knowledge I can get.” Then she straightened up; her face moved back into the shadows and once again became that of a little girl.

Craig swallowed hard. “If I can get your answer without causing any pain, I’ll do it.”

“That’s a fair enough trade. I’ll be waiting for you right here. And I’ll play a song to ease old Mr. Foyt on his way. You can call it a prayer, if you like.”

“Thank you.” Craig turned and headed up the hill, resisting the urge to look back and see if the little girl remained, or if the old gnome who spoke with her voice had returned. He wondered which was her true face.

Mrs. Pennycuff admitted him to the small, neat farmhouse with a grateful hug. Two of her siblings, along with a teenage grandson, sat numbly in the living room. Labored, raspy breathing came from one of the bedrooms, and Mrs. Pennycuff quickly escorted Craig inside.

The light was low, but there was enough to easily see Mr. Foyt was indeed on his way out of this world. An oxygen tank with dinged paint stood in the corner, feeding the mask over the old man’s nose and mouth. Another adult child, a daughter, sat beside him and held his hand. She leaned close to his ear and said loudly, “The preacher is here, Daddy. I’m going to let him sit down here.”

She stood and held on to her father’s hand until Craig was settled. Then, even after Craig took the dry fingers in his own, she patted the hand and said, “I love you, Daddy.”

Craig put his Bible on the old man’s chest, and helped him find it with his other hand. Foyt let out a wheezy but contented sigh. “Thank you, preacher,” he said in a thin, whispery voice.

“Glad to do it. I’m not a Catholic, Mr. Foyt, so I’m not going to ask for confession or grant you absolution. But if there’s anything you want to tell me, it will go no farther than this room. Otherwise, I think I’ll just sit here and pray with you a bit.”

“That’s all I need, preacher,” Foyt said. His breathing was easier now. “The Lord knows my heart, and I’ll be judged on that. He’s waiting for me. I can feel Him out there, like when you know a bluegill’s sniffing around your bait.”

Craig admired the certainty of that simple faith. He believed in God, but not this way. His way was complicated by knowledge, thought, and a sense of how the world worked outside these mountains.

He sat silently for a long time, listening to Old Man Foyt breathe and the soft hiss of the oxygen. At last he said, “Mr. Foyt? I have a question to ask you. You don’t have to answer if you don’t want to.”

“Go ahead,” came the slow, faint reply.

“You know the Tufa, right? You’ve been around them all your life. You live in Cloud County, even. Do you believe . . .”

He checked to make sure none of the relatives had slipped in, or lurked at the door. But no, he could hear them murmuring and crying in the other room. He and Foyt were alone.

“. . . that the Tufa will appear before the same God as you will?” he finished.

The moment before the response was the longest of Craig’s life. There was no reason this unlettered, unschooled farmer should have any great insight into these spiritual matters, except for the coincidence of timing and geographic location. Could this simple Christian, who believed God stood waiting for him and who happened to be dying in a place where Christianity had never taken hold, give him insight directly from the Lord, about people who didn’t believe in Him?

Then Foyt said, “Here’s what the Lord just told me, preacher . . .”

The ambulance came at dawn to take Mr. Foyt’s body to the funeral home in Unicorn. He’d be buried in the cemetery attached to Craig’s church, and the family had already asked him to give the eulogy. He asked them to tell stories about the deceased, and before long all of them were alternately laughing and crying.

By the time Craig came down the hill to his car, it was full daylight, although the morning mist still covered the land. He was exhausted, and wanted nothing more than a shower and some sleep, in that order. Then he remembered Bronwyn’s offer of breakfast, and smiled at the thought of seeing her.

But there was Mandalay, still seated on the fence, holding but not playing her tiple. In the haze she looked entirely human, entirely a child. Not even her eyes gave away anything otherworldly. But after last night, they didn’t have to.

“Morning,” Craig said. “You been here all night?”

“I have.”

“Your parents must be worried.”

“They know where I am.” She paused. “Did you ask?”

“I did.”

She yawned, then climbed down and walked across the road to stand before him. The morning birds twittered in the trees, and cows hidden by the fog lowed their contentment. She looked up at him and said with what had to be forced casualness, “Well, what did he tell you?”

Craig swallowed for a moment. “He said . . . ‘It’s just like Bob Marley said.’”

At first Mandalay did not react. Then she nodded, turned, and walked away.

When Foyt had spoken, Craig had been almost totally certain he’d heard wrong. After all, how would this old white man, who’d spent his whole life in Appalachia amongst the whitest music around, know anything other than the name of Bob Marley, let alone a quote? He’d faded after that, unable to answer any of Craig’s follow-up questions about precisely what Bob Marley had said, and about what.

As the paramedics removed the body and the family prepared for visitation, Craig had surreptitiously looked for albums, CDs, or even eight tracks that might explain the statement. But there hadn’t been a single hint of music that wasn’t American country or white gospel.

The only obvious explanation was, of course, that Foyt had relayed the actual words of God. And that, like the idea that the Tufa were fairies, was bigger than Craig could accept all at once.

“Wait,” Craig called after the girl. “I mean . . . does that make sense to you?”

She stopped and turned. For an instant, he thought he saw the shape of delicate, beautifully sheer wings in the hazy air.

“It does,” she said. “Do you know Bob Marley?”

“So he meant something like, ‘No woman no cry’? ‘Let’s get together and feel all right’?” He chuckled, from weariness and puzzlement. “‘I shot the sheriff’?”

“No, not his music. Something he said once. He said, ‘I don’t stand for the black man’s side, I don’t stand for the white man’s side, I stand for God’s side.’” Then she resumed walking off into the morning, the tiple over her shoulder. Before she’d gone five steps, she vanished.

“Shall We Gather” copyright © 2013 by Alex Bledsoe

Art copyright © 2013 by Jonathan Bartlett